This dialog contains the full navigation menu for this site.

Hayfield House, today: humming with administrative activity as faculty and staff work to serve Penn State Wilkes-Barre students.

Hayfield House, 1930s to 1960s: home of a very wealthy couple who wanted to enjoy time and entertain their friends, including members of the “Who’s Who” of New York City society.

Hayfield House, today at the heart of Penn State Wilkes-Barre, was built as a summer home for wealthy couple John and Bertha Conyngham. John was a superintendent at his family’s coal-mining business, “one of the best versed men in the anthracite industry and one of the most prominent in the coal trade,” according to The Evening News, a predecessor of the Times Leader. Bertha was a New York City socialite and heiress, the daughter and stepdaughter of wealthy, prominent bankers who worked for Drexel, Morgan and Co.

The couple married in 1895 at Bertha’s mother’s home on Fifth Avenue in New York. They were “married very quietly,” as written about in The New York Times, on account of the recent death of Bertha’s stepfather. Their guests included Mr. and Mrs. J. Pierpont (J.P.) Morgan, whose gift to the couple was a large double star of diamonds, an ornate pendant. After their honeymoon in Europe, the Conynghams split their time between a mansion on River Street in downtown Wilkes-Barre, John’s parents’ wedding present to them, later donated to the forerunner of Wilkes University and destroyed by fire in the 1970s, and a suite of rooms at the Plaza Hotel in New York City. They also spent a good amount of time abroad, particularly in France.

Beginning in 1910, the Conynghams purchased several smaller farms in Dallas, amassing a total of more than 900 acres. Wanting to escape the heat of the city and enjoy a country respite, they used one of the farmhouses as a small home and base of operations during the construction of Hayfield House. Hayfield House was built at a cost of more than a million dollars, equivalent to more than $23 million in today’s dollars. (The original farmhouse, which would have been considered an upscale starter home, can still be seen from Hayfield House, looking out back toward the east.)

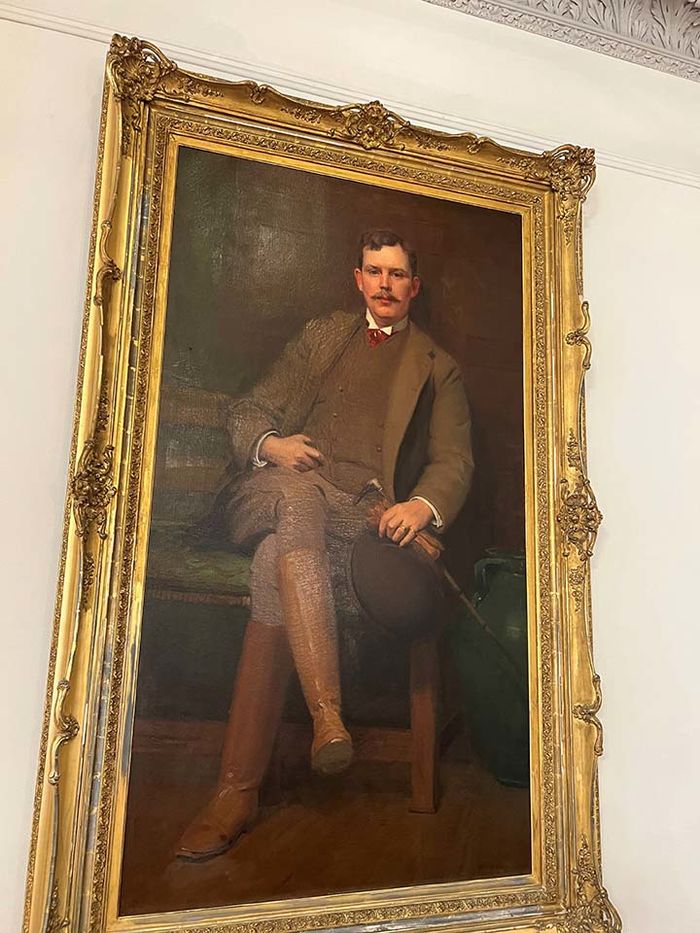

This painting of John Conyngham hangs in Room 105 of Hayfield House today.

This painting of Bertha Conyngham hangs in Room 105 of Hayfield House today.

The home was built during the Great Depression, but John and Bertha Conyngham belonged to a set of society mostly untouched by the financial troubles that overwhelmed much of the country. They believed their wealth came with a certain responsibility to give back to their community and did so by providing jobs to local residents. The stipulations for the building of the home gave directions for using as much local labor as possible. The large acreage of the estate also provided an employment opportunity for local farmers who were unable to sell their crops to help clear the fields at Hayfield. In clearing those fields, they dug up much of the fieldstone used to build the house.

Construction on Hayfield House, designed in the Colonial Revival style, began in 1932. The home was named after John’s great-grandfather, David Hayfield Conyngham, “whose interest as to humanity and altruism in Philadelphia has carried through the generations,” according to The Evening News.

Local residents were extremely curious about the construction of the mansion and were able to read an article in The Wilkes-Barre Record, a local newspaper at the time, that elaborated on the home, providing a description of the décor and colors of each room in detail. “From the winding road leading to the entrance of the estate the massive, sombre-toned walls with contrasting white pillars may be glimpsed as it towers above the broad sweep of rolling lawns, the flowers and shrubbery. No hint of ostentation, no pretension; just serene and pleasing to the senses. For Hayfield House may well be regarded as the epitome of restraint, of unerring good taste,” the newspaper wrote on June 16, 1934.

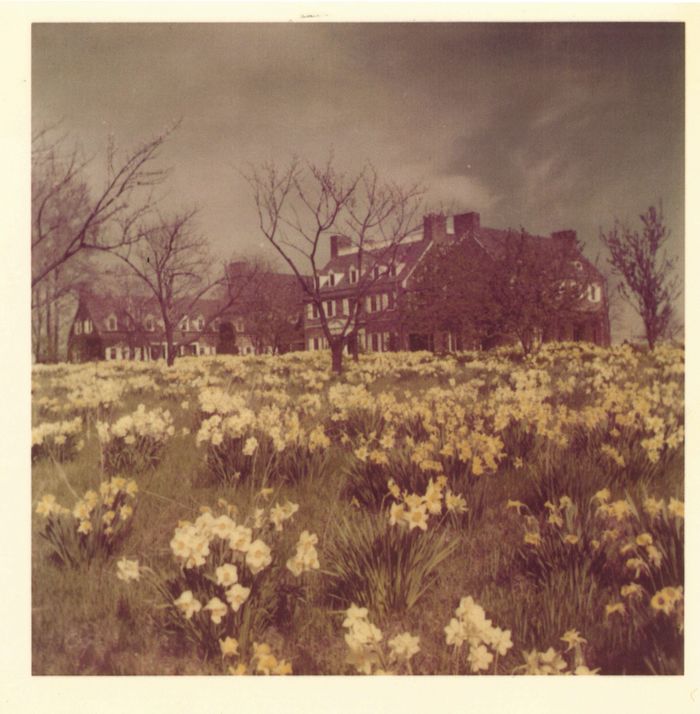

An undated image of the exterior of Hayfield House.

Hayfield House was also featured in two publications in Country Life magazine in 1935, one about the interior and one about the farm, both featuring several spreads of photos. “The house, though colonial in inspiration, somehow gives the impression of an old baronial estate—quite in keeping with the fact that the Conynghams are of British descent,” the magazine wrote.

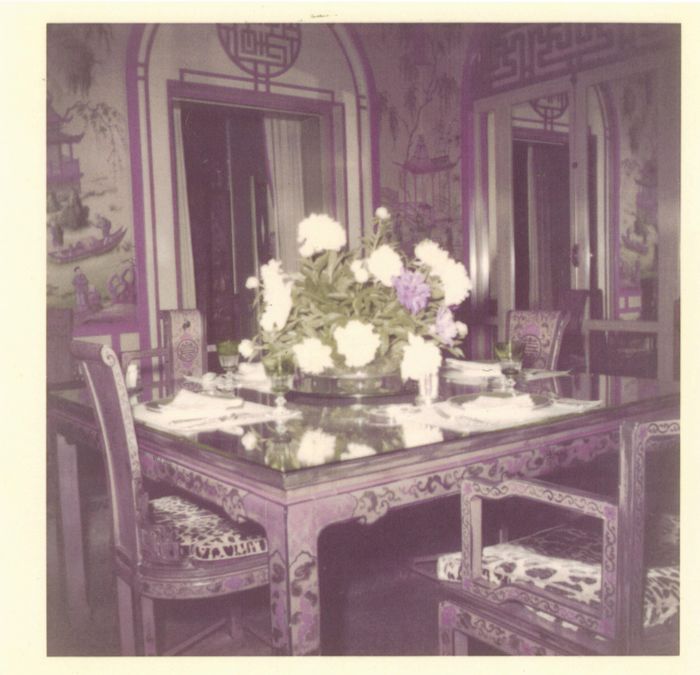

The antiques and ornate architectural features ensured the home was a showpiece for the family. Each room had its own style. Skilled craftsmen were brought in from Europe to provide certain elements the Conynghams wanted in the home, including carvings and wall coverings. The couple also went on a world buying tour to purchase items for Hayfield House. Those included stained glass windows from a cathedral in Paris that were installed in the library; columns dating to the 16th century from a wealthy family’s home in England; and a fireplace from a castle on the Rhine River that was reassembled in Hayfield House. That fireplace is today in Room 105 across from its mate, created by marble artisans as a duplicate of the original. Today, instead of welcoming the guests of a chamber music concert, the room serves as the setting for advisory board meetings, student award ceremonies and more. The breakfast room at the home was designed using handpainted Chinese wall paper similar to the Sleeper-McCann House in Gloucester, Massachusetts, the summer home of one of the first professional interior designers in American. Bertha’s bedroom—today the chancellor’s office—was modeled after the boudoir of Marie Antoinette at Versailles. Mirrors were strategically placed to reflect the landscape and the lighting. The bathtub, sink and lights from Bertha’s sink still remain in offices at the campus.

While Hayfield House featured numerous antiques, it was constructed with the modern conveniences of the 1930s, including a coal furnace, hot water, electricity, air conditioning and burglary and fire alarm systems. From the beginning, the house was fully electrified. The air conditioning system used the well head in front of where the Nesbitt Academic Commons building is today. Water (about 53 degrees) from underground was pumped into the basement of Hayfield House, where a network of metal water lines and fans was also established. The water would flow through the lines toward the fans, which cooled the water even more and also directed cool air up into the house. If there was a concern about the house being broken into, John could press a button located on his side of the bed in the master bedroom, which now serves as a conference room, and a light would turn on in each room of the house. The home also had a fire alarm siren that could be rung and heard in Dallas, 6 miles away.

The Conynghams first occupied the house for Thanksgiving in 1933. In June 1934, the couple welcomed several hundred guests, including those from New York, Philadelphia and Baltimore, for a housewarming party that included dinner and dancing. Guests would be driven to the mansion’s front door along the circular driveway and be led into the stunning entryway with its floating staircase at the center. It was by design that the house felt grand and lavish when guests entered. Freshly cut flowers from the greenhouse on the property were placed in many rooms daily.

The home was built with 20 bedrooms and almost as many bathrooms—far more than the two people living there needed, and during a time when many people were still using outhouses. But in the Conynghams’ world, it was commonplace to invite friends to stay for a weekend, or even a week or two. Their friends would travel by train, often from large cities, for a country respite. Guests were able to enjoy their own rooms, closets and bathrooms. If the Conynghams ran out of room in Hayfield House during a larger event, guests were put up at the Hotel Sterling in downtown Wilkes-Barre, and chauffeurs would make the 14-mile trip to drive them back and forth between the hotel and the house.

Even royalty came to Hayfield House. In 1935, Princess Aymon de Faucigny Lucinge of France (Carolyn Foster prior to marriage) was a guest at the home. The Evening News noted she had “recently arrived from Paris and was to spend the summer in Bretton Woods, New Hampshire.” The Conynghams also spent time during the summers in Bretton Woods, located in the White Mountains, at the Mount Washington Hotel that John funded. The hotel was built by Joseph Stickney, Carolyn Foster’s first husband, who had worked with John and his father in Wilkes-Barre. After Stickney died, Foster married a French prince and remained friends with the Conynghams.

As the home was built as a showpiece of the Conynghams’ wealth, status and interests, they were happy to offer tours and luncheons to various local organizations, including the Wilkes-Barre Garden Club and Luzerne County Agricultural Extension Association.

John’s love of farming and the outdoors is evident in the detail in the building. His study contained carvings of animals and nature scenes in the wood trim and in the wallpaper, a reminder of why the couple planned to spend their summers in northeastern Pennsylvania: to enjoy nature and the beautiful scenery. Those carvings can still be seen in the room today.

An undated image of the breakfast room inside Hayfield House.

The farm was a signature element of the estate, providing John Conyngham with an outlet for his vast interests in animals. He wanted to have a farm where he could experiment with a variety of fruit production, including a peach orchard, as well as animals ranging from Scottish highland cattle to Chester white pigs to Sardinian donkeys. He also raised some of the country’s original breeding stock of Clydesdale horses—ancestors of the present-day Budweiser Clydesdales.

In addition to the farm, the estate included a 19-car garage, built to house John’s extensive car collection. Two of his vehicles were Lincoln Continentals that were custom made, with their tops raised higher than normal so John could get in and out of the car without having to remove his top hat.

The Conynghams were connected in their community, particularly since John and his family had a long lineage in northeastern Pennsylvania. He was president of United Charities of Wilkes-Barre and the Luzerne County Humane Association; director and treasurer for Wilkes-Barre General; a board member of Miners Bank and the National Biscuit Company (later Nabisco); and a member of the Wyoming Historical and Geological Society, among others. They were members of St. Stephen’s Episcopal Church along with social organizations including the Westmoreland Club, the Union League Club, the Metropolitan Club, the New York Yacht Club and the Piping Rock Club in New York City.

When the local fire department in Lehman wanted to raise money for a new fire truck after World War II, fire department leaders had an idea to ask Bertha to contribute $12,500—half the cost of the vehicle. When they met with her and explained the need, she offered to pay the entire $25,000 on one condition: She wanted to have the first ride and ring the bell. The fire department took her up on her generous offer and rewarded her with that ride.

The Conynghams had no children but helped raise Bertha’s two nephews, Richard and Edward Robinson, upon their parents’ deaths nine days apart in December 1909 and January 1910. Edward was 15 and Richard was 5 when they were orphaned. Richard spent his time with the Conynghams when not at boarding school.

A home and estate as large as the Conynghams’ required a staff of servants to keep things running smoothly and efficiently. Employees who took care of the operations inside the home when the family was in residence from May to November included a butler, a cook, a cook’s helper, a serving maid, a parlor maid, a chamber maid, Bertha’s personal maid, nurses, an estate manager and a chauffeur. Additionally, about 20 farm workers and several grounds maintenance and security employees took care of the exterior of the property. During the winter months, several men were left at the estate to continue operating the hand-fired coal stoves and a few women also remained in the home to clean.

The 1930s were a time of change, when hiring servants could be difficult. It is likely that the Conynghams’ servants had the option to travel from their own homes or stay at Hayfield House. Female servants slept in the women’s quarters and male servants in the men’s quarters. The chauffeur lived above the garage.

The numerous guests who visited from out of town brought their own servants, who were housed on the third floor of Hayfield House in an area designed for visiting staffs. When guests arrived, their servants would bring in their employer’s luggage, likely through the servants’ entrance on the side of the house.

John Conyngham had a heart attack in Hayfield House on July 2, 1935, and passed away there 10 days later. Bertha continued to spend summers in the home until her death nearly 30 years later. Knowing the house and estate had been a great passion of her husband’s, she kept coming every summer after he died. She continued to entertain and participate in various local organizations and charities. During the off-season, when she was living in a seven-room apartment at the Plaza Hotel in New York, she would call the gardener at Hayfield House to request certain flowers. The flowers would be cut from the greenhouse on the estate, boxed up and sent on the next train from Wilkes-Barre to New York.

Bertha Conyngham died August 12, 1964. Both she and John are buried in the Woodlawn Cemetery, in the Bronx, New York, where several members of Bertha’s family are also interred. Their wills included bequests to relatives, friends, Wilkes-Barre General Hospital, St. Stephen’s, the Wilkes-Barre Children’s Home, the Wilkes-Barre YMCA and the Wilkes-Barre Department of Public Works.

After Bertha died, a sale of the home’s inventory was advertised worldwide. Although many of the items were sold, a number of artifacts from the Conynghams’ time remain at Penn State Wilkes-Barre today.

She left Hayfield House and the estate to her nephew, Richard Robinson, at the time a resident of Connecticut. He donated the house and about 50 acres to Penn State Wilkes-Barre. The campus, which had previously had held classes at a number of locations throughout the Wyoming Valley since 1916, established Hayfield House as its permanent home in 1968. At the beginning, classes were held in Hayfield House, which is now used for administrative, faculty and staff offices. The 19-car garage was turned into a student center and cafeteria, and several other classroom buildings have been constructed since then.

Throughout its history, both as the Conynghams’ home and as a campus serving thousands of students from northeastern Pennsylvania and beyond, Hayfield House has been a place where people form and strengthen connections with others and with their community. Penn State Wilkes-Barre is proud to occupy and preserve such a historic and stately home, and looks forward to continuing a future with Hayfield House at the center of the campus.

Special thanks to Molly Abdalla, assistant librarian, student engagement and outreach services; Bill Bachman, instructor, communication arts and sciences; Megan MacGregor, former librarian, student engagement and outreach services; and Jonathan Pineno, lecturer of music and art, for sharing their knowledge and research for this article.